Some businesses bleed black

Many successful businesses have played by an entirely different set of rules.

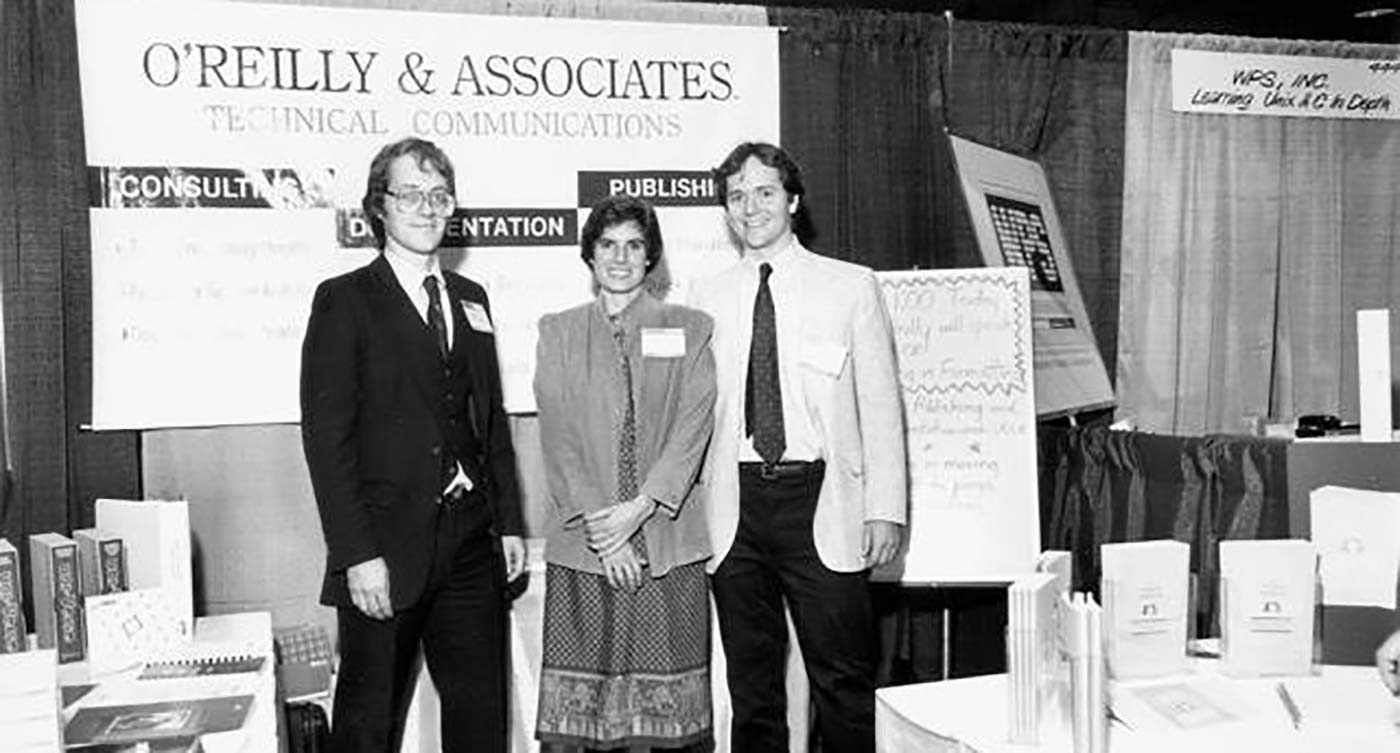

Tim O'Reilly, Nancy Dougherty, and Dale Dougherty, in 1985 or so, ready to sell some of O'Reilly's first books (over on the right) to customers. (source: Tim O'Reilly)

Tim O'Reilly, Nancy Dougherty, and Dale Dougherty, in 1985 or so, ready to sell some of O'Reilly's first books (over on the right) to customers. (source: Tim O'Reilly)

It’s hard to argue with Reid Hoffman. His Masters of Scale podcast is a masterpiece. Even when you might think he’s wrong, he’s persuasive. He sees the complexity in every situation, and is reluctant to give simple answers. His advice is always insightful and actionable.

And in Episode 2 — “The Money Episode” — Reid weaves a wonderful set of stories from serial entrepreneurs Mariam Naficy and Selina Tobaccowala about why it’s always a good idea for entrepreneurs to take more money than they think they need. He even covers his bases with Brian Chesky’s counterargument that having less money than you need forces greater creativity, and that too much money can make companies lazy and arrogant. So the case really seems airtight. Not only that, everything Reid says seems true to me! I could match him story for story from my own business career and from that of friends to demonstrate the dangers of not having enough money, and I could match Brian story for story on the dangers of having too much at the wrong time.

And yet, and yet…

Reid contrasts the “blitzscaled” businesses so dear to venture capitalists with “lifestyle businesses” whose model is predictable but will never bring the kind of high returns that only come with placing big, bold bets. He neglects to mention that there is a huge gap between these two extremes that is full of successful businesses that have played by an entirely different set of rules.

I’ve run a business for nearly thirty-five years that never took a dime of money from investors (unless you count the time in early days when my mom bailed me out with an emergency $10,000 loan), that is approaching $200 million in revenue, and that has had a huge impact on the success of Silicon Valley. When in 2000, the cover of Publishers Weekly announced “The Internet was built on O’Reilly books,” no one disagreed. We’ve helped fuel and frame the commercial internet, the open source software movement, “Web 2.0,” the maker movement, and government technology innovation. Along the way, we morphed from a technical writing consulting company into a publisher, which also happened to launch the first commercial website, pioneered ebooks, built a hugely successful conference business, melded ebooks and events into an integrated media business, and operates one of the largest and most successful online professional learning platforms, combining ebooks, video, live online training, and more.

Customers have funded the company, and we’ve never been able to grow without satisfying them.

Our secret: build products that people love, and are willing to pay for. Price those products fairly; be generous not just with customers but also with resellers and even competitors. Focus not on hypergrowth, but instead on sustainable cash flow and profits, growing at the rate that customers are willing to fund with their purchases, keeping a tight rein on expenses, and playing for the long haul. Keep reinvesting cash flow and profit back into the business. Build an ecosystem to extend your reach. Talk less about your products, and more about the big ideas behind them, creating new business categories that enable others, even bringing in new competitors. Partner aggressively, creating value for suppliers, resellers, and partners, all of whom succeed when you do. Use bank debt, collateralized by receivables, inventory, or other assets, to bridge the gap between what you have in hand and what you need for that next increment of growth. Find markets where time is an ally rather than an enemy, because there will always be a need for what you do. Have a vision (ours is “changing the world by spreading the knowledge of innovators”) and pivot within that vision, constantly finding new opportunities to express it. When you come across an opportunity that is growing too fast to fund out of operating cash flow, spin it out into an independent entity that can seek funding of the type Reid champions. And if you decide that an opportunity isn’t as big as you thought, don’t be afraid to move on.

None of this is easy. No business is. But as Paul Hawken once wrote, “Every business has problems. The difference between a good business and a bad business is that a good business has interesting problems.” O’Reilly Media has always been interesting, because we’ve always worked on things that we were passionate about, and we never had to worry about whether we were doing the things that would please investors.

We aren’t alone. REI began with funding from 23 people each of whom paid the grand sum of $1 to join the coop. It now has $3.2 billion in revenue, and outperforms all its peers in growth and same-store sales. “But that’s not tech!” you might complain. OK. Let’s start with some multi-billion dollar giants that were funded by customer cash flow: Microsoft, Bloomberg, ESRI, Epic Systems, SAS, and Dell. Some less august examples include Adafruit, Basecamp, Atlassian, Shutterstock, Craigslist, Lynda.com, Github, Mailchimp, SurveyMonkey, and Zoho. Some of these companies have gone public; others have been sold at valuations the envy of any VC; some are still private. Some took in investors later, but that was part of a process aimed to take them public rather than as the kind of necessary investment that Reid talks about in this podcast.

All of this is by way of saying that while Reid is right that if you are taking money from investors, you should almost always take more than you think you need, there is a third way, that involves not taking money from investors at all.

At O’Reilly AlphaTech Ventures (OATV), the early stage venture firm where I am a partner along with Mark Jacobsen and Bryce Roberts, we’ve been trying to spread the idea that not every business is the nail to be driven by the venture capitalist’s hammer. Bryce has come up with a unique model, which he calls indie.vc, that offers a unique bridge between Silicon Valley venture capital and the customer funded model practiced by O’Reilly Media and the other companies listed above. We provide seed funding in the form of a loan that can be paid back through cash dividends once the company succeeds, or convert to equity if and only if the entrepreneur later decides that raising capital for fast scaling is more appropriate for the company.

As Bryce put it, “At Indie.vc, we believe that companies with a focus on making a product customers love and selling it at a profit from the very beginning have a distinct long term advantage over those who don’t. We’ll trade slower, thoughtful, compounding growth over scaling fast and failing fast every time….The freedom and benefits of that focus are manifest in every aspect of a company’s culture. Startups bleed red, real businesses bleed black.”

I might change Bryce’s last line to read: “Don’t assume that every business has to bleed red. Some businesses bleed black.” But even in those businesses, Reid is ultimately right. Whether you get your cash from operations or from investors, having enough of it to meet the unexpected can make all the difference between success and failure.

I’d love to hear from more of you who’ve built cash-flow positive businesses that have grown large over time, or ones that have stayed small but have made happy customers and happy employees. Entrepreneurs need role models for every type of business, and forums like this one are a great way to share what we’ve learned.