D-Day in Kyiv

Fractal art. (source: Pixabay)

Fractal art. (source: Pixabay)

My experience working with Ukraine’s Offensive Cyber Team

By Jeffrey Carr

March 22, 2022

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24th, I had been working with two offensive cyber operators from GURMO—Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine—for several months trying to help them raise funds to expand development on an OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) platform they had invented and were using to identify and track Russian terrorists in the region. Since the technology was sensitive, we used Signal for voice and text calls. There was a lot of tension during the first few weeks of February due to Russia’s military buildup on Ukraine’s borders and the uncertainty of what Putin would do.

Then on February 24th at 6am in Kyiv (February 23, 8pm in Seattle where I live), it happened.

SIGNAL log 23 FEB 2022 20:00 (Seattle) / 24 FEB 2022 06:00 (Kyiv)

Missed audio call - 8:00pm

It started 8:01PM

War?

9:36PM

Incoming audio call - 9:37PM

Call dropped.

9:41PM

Are you there?

9:42PM

I didn’t hear from my GURMO friend again for 10 hours. When he pinged me on Signal, it was from a bunker. They were expecting another missile attack at any moment.

“Read this”, he said, and sent me this link. “Use Google Translate.”

It linked to an article that described Russia’s operations plan for its attack on Ukraine, obtained by sources of Ukrainian news website ZN.UA. It said that the Russian military had sabotage groups already placed in Ukraine whose job was to knock out power and communications in the first 24 hours in order to cause panic. Acts of arson and looting would follow, with the goal of distracting law enforcement from chasing down the saboteurs. Then, massive cyber attacks would take down government websites, including the Office of the President, the General Staff, the Cabinet, and the Parliament (the Verkhovna Rada). The Russian military expected little resistance when it moved against Kyiv and believed that it could capture the capital in a matter of days.

The desired result is to seize the leadership of the state (it is not specified who exactly) and force a peace agreement to be signed on Russian terms under blackmail and the possibility of the death of a large number of civilians.

Even if part of the country’s leadership is evacuated, some pro-Russian politicians will be able to “take responsibility” and sign documents, citing the “escape” of the political leadership from Kyiv.

As a result, Ukraine can be divided into two parts—on the principle of West and East Germany, or North and South Korea.

At the same time, the Russian Federation recognizes the legitimate part of Ukraine that will sign these agreements and will be loyal to the Russian Federation. Guided by the principle: “he who controls the capital—he controls the state.”

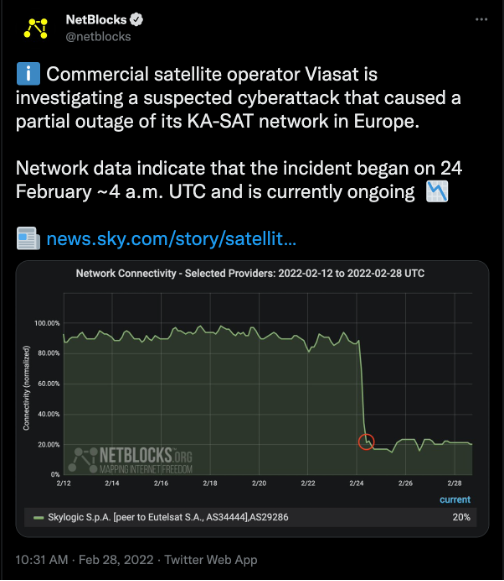

The first significant Russian cyber attack of the war is suspected to be the one that took down satellite provider ViaSat at precisely 06:00 Kyiv time (04:00 UTC), the exact time that Russia started its invasion.

The cause is believed to be a malicious firmware update sent to ViaSat customers that “bricked” the satellite modems. Since ViaSat is a defense contractor, the NSA, France’s ANSSI, and Ukrainian Intelligence are investigating. ViaSat hired Mandiant to handle digital forensics and incident response (DFIR).

“Is Ukraine planning to retaliate?”, I asked.

“We’re engaging in six hours. I’ll keep you informed.”

That last exchange happened about 22 hours after the start of the war.

FRIDAY, FEB 25, 2022 07:51

I received a Signal alert.

“Download ready” and a link.

The GURMO cyber team had gained access to the accounting and document management system at Russian Military Unit 6762, part of the Ministry of Internal Affairs that deals with riot control, terrorists, and the territorial defense of Russia. They downloaded all of their personnel data, including passports, military IDs, credit cards, and payment records. I was sent a sampling of documents to do further research and post via my channels.

The credit cards were all issued by Sberbank. “What are you going to do with these”, I asked. He sent me a wink and a grin icon on Signal and said:

Buy weapons and ammo for our troops!

We start again at 6:30am tomorrow.

When you wake up, join us.

Will do!

Over the next few days, GURMO’s offensive cyber team hacked a dizzying array of Russian targets and stole thousands of files from:

- Black Sea Fleet’s communications servers

- ROSATOM

- FSB Special Operations unit 607

- Sergey G. Buev, the Chief Missile Officer of the Ministry of Defense

- Federal Air Transport Agency

Everything was in Russian, so the translation process was very time-consuming. There were literally hundreds of documents in all different file types, and to make the translation process even harder, many of the documents were images of a document. You can’t just upload those into Google Translate. You have to download the Google Translate app onto your mobile phone, then point it at the document on your screen and read it that way.

Once I had read enough, I could write a post at my Inside Cyber Warfare Substack that provided information and context to the breach. Between the translation, research, writing, and communication with GURMO ,who were 11 hours ahead (10 hours after the time change), I was getting about 4 ½ hours of sleep each night.

We Need Media Support

TUESDAY, MARCH 1, 2022 09:46 (Seattle)

On Signal

We need media support from USA.

All the attacks you mentioned during these 6 days.

We have to make headlines to demoralize Russians.

I know the team at a young British PR firm.

I’ll check with them now.

Nara Communications immediately stepped up to the challenge. They agreed to waive their fee and help place news stories about the GURMO cyber team’s successes. The Ukrainians did their part and gave them some amazing breaches, starting with the Beloyarsk Nuclear Power Plant—the world’s only commercial fast breeder reactors. Other countries were spending billions of dollars trying to achieve what Russia had already mastered, so a breach of their design documents and processes was a big deal.

The problem was that journalists wanted to speak to GURMO and that was off the table for three important reasons:

- They were too busy fighting a war to give interviews.

- The Russian government knew who they were, and their names and faces were on the playing cards given to Kadryov’s Chechen Guerillas for assassination.

- They didn’t want to expose themselves to facial recognition or voice capture technologies because…see #2.

Journalists had only a few options if they didn’t want to run with a single-source story.

They could speak with me because I was the only person who the GURMO team would directly speak to. Plus, I had possession of the documents and understood what they were.

They could contact the CIA Legat in Warsaw, Poland where the U.S. embassy had evacuated to prior to the start of the war. GURMO worked closely with and gave frequent briefings to its allied partners, and they would know about these breaches. Of course, the CIA most likely wouldn’t speak with a journalist.

They could speak with other experts to vet the documents, which would effectively be their second source after speaking with me. Most reporters at major outlets didn’t bother reporting these breaches under those conditions. To make matters worse, there were no obvious victims. The GURMO hackers weren’t breaking things, they were stealing things, and they liked to keep a persistent presence in the network so they could keep coming back for more. Plus, Russia often implemented a communications strategy known as Ихтамнет (Ihtamnet), which roughly translated means “nothing happened” or to put it into context “What hacks? There were no hacks.”

In spite of all those obstacles, Nara Communications was successful in getting an article placed with SC magazine, a radio interview with Britain’s The Times, and a podcast with the Evening Standard.

By mid-March, Putin showed no signs of wanting peace, even after President Zelensky had conceded that NATO membership was probably off the table for Ukraine, and GURMO was popping bigger targets than ever.

The Russians’ plan to establish a fully automated lunar base called Luna-Glob was breached. Russia’s EXOMars project was breached. The new launch complex being built at Vostochny for the Angara rocket was breached. In every instance, a trove of files was downloaded for study by Ukraine’s government and shared with its allies. A small amount was always carved out for me to review, post at the Inside Cyber Warfare Substack, and share with journalists. Journalist Joe Uchill referred to this strategy as Hack and Leak.

Hack and Leak

By hacking some of Russia’s proudest accomplishments (its space program) and most successful technologies (its nuclear research program), the Ukrainian government is sending Putin a message that your cybersecurity systems cannot keep us out, that even your most valuable technological secrets aren’t safe from us, and that if you push us too far, we can do whatever we want to your networks.

Apart from the attack on ViaSat, there hasn’t been evidence of any destructive cyber attacks against Ukrainian infrastructure. Part of that was strategic planning on the part of Ukraine (that’s all that I can say about that), part was Ukraine’s cyber defense at work, and part of that may be that GURMO’s strategy is working. However, there’s no sign that these leaks are having any effect on impeding Russia’s military escalation, probably because that’s driven out of desperation in the face of its enormous military losses so far. Should that escalation continue, GURMO has contingency plans that will bring the war home to Russia.

Jeffrey Carr has been an internationally-known cybersecurity adviser, author, and researcher since 2006. He has worked as a Russia SME for the CIA’s Open Source Center Eurasia Desk. He invented REDACT, the world’s first global R&D database and search engine to assist companies in identifying which intellectual property is of value to foreign governments. He is the founder and organizer of Suits & Spooks, a “collision” event to discuss hard challenges in the national security space, and is the author of Inside Cyber Warfare: Mapping the Cyber Underworld (O’Reilly Media, 2009, 2011).